CMYK: 권세진 Sejin Kwon

파란 하늘과 뭉게구름, 빛을 반사하는 황금빛 모래알, 고요히 흘러가는 강물, 유리창을 뚫고 실내를 비추는 햇살, 빠르게 달리는 버스 차창 너머의 노을. 어딘지 좀 슬픈 풍경이다. 시간의 지배를 받는 세계에서 우리는 그저 잠시 만났다가 헤어질 뿐이다. 아직 기적적으로 살아있는 우리에게 풍경들이 와락 안기다가 곧 사라진다. 이 무정하고 속절없는 세계를 견디기 위해 인간은 그렇게 이미지를 만들어 냈나 보다. 이미지(Image)의 어원은 죽은 이의 영정사진과 같은 밀랍 가면을 지칭하는 ‘이마고(Imago)’이며, 형상(Figure)의 어원은 귀신을 뜻하는 ‘피구라(Figura)’인 이유가 여기에 있다. 사라질 것들을 이미지로라도 붙들어 놓으려는 욕망의 역사가 바로 미술의 역사다.

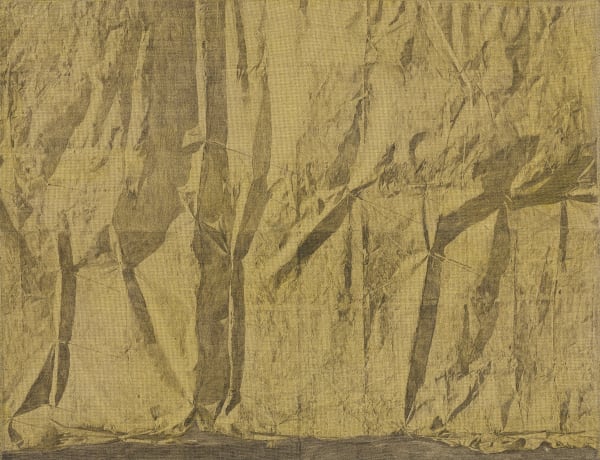

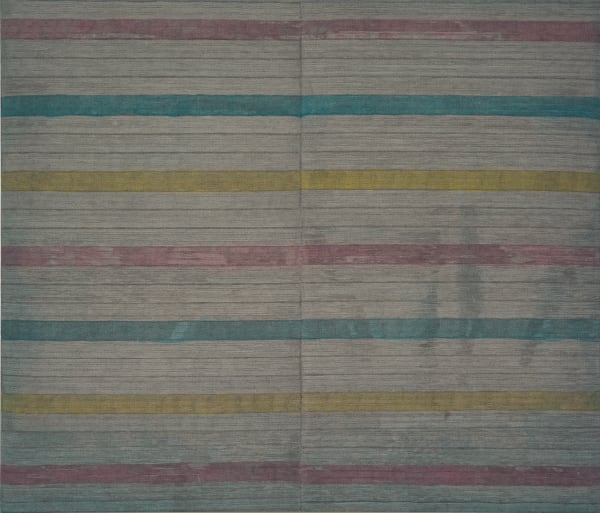

권세진은 이번 개인전 <CMYK>에서 탁본 방식을 응용한 풍경화를 보여준다. 캔버스 위에 먹지를 대고 그 위에 종이로 인쇄한 풍경 사진을 맨 위에 올려놓은 뒤 모나미 볼펜이나 BIG펜으로 이미지의 음영과 형태를 그린다. 아니 그린다기보다는 ‘마킹’한다는 표현이 더 적절할 것이다. 이 과정이 끝나면 채색 단계에 들어간다. 색을 섞지 않고 잉크젯 프린트의 인쇄 방식인 CMYK 즉, 청록색의 사이안(Cyan), 선홍색의 마젠타(Magenta), 노란색의 옐로우(Yellow), 검은색의 키 플레이트(Key Plate) 색상만을 이용해 채색했다. 여기서 ‘K’는 먹지에 해당하니 실제로는 CMY의 세 가지 색만 사용한 것이다. 처음에는 세밀한 부분을 먼저 채색하고 마지막에는 평붓으로 화면 전체를 쓸어주며 색을 입혔다.

2014년부터 권세진은 이미지를 화면에 옮길 때 먹지를 사용했다. 그는 먹지 위에 인쇄한 사진을 올려 놓고 따라 그리는 방식을 제일 좋아하는 데, 이유는 최대한 작가의 주관성을 배제한 기계적인 방식이기 때문이라고 한다. 그러나 이것은 그저 ‘덜’ 주관적인 방식일 뿐이다. 먹지를 대고 그릴 때 사진 이미지를 프린트하는 종이의 두께, 이미지를 마킹하는 캔버스의 재질, 볼펜의 종류, 마킹할 때의 팔의 힘 조절 등 여전히 작가가 선택해야 할 것이 많다. 먹지 작업은 캔버스 화면 위에 사진 이미지를 정확하게 옮겨 놓을 수 있지만, 먹지는 한 번 사용하면 다시 색이 배어나지 않기 때문에 여러 번 선을 쌓아가면서 깊이감을 만들 수 없고 오로지 힘의 강도로 조절해야 한다는 단점도 있다고 한다.

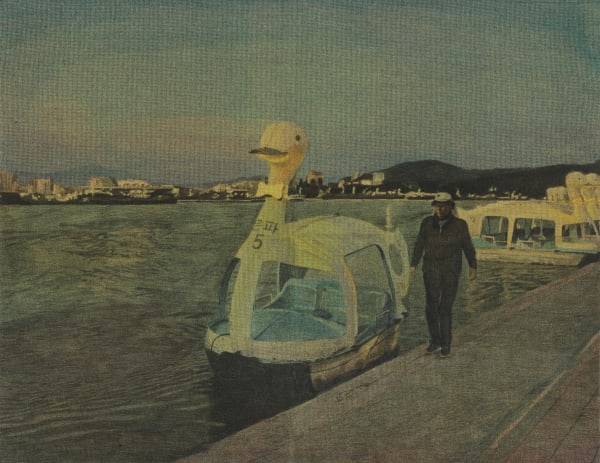

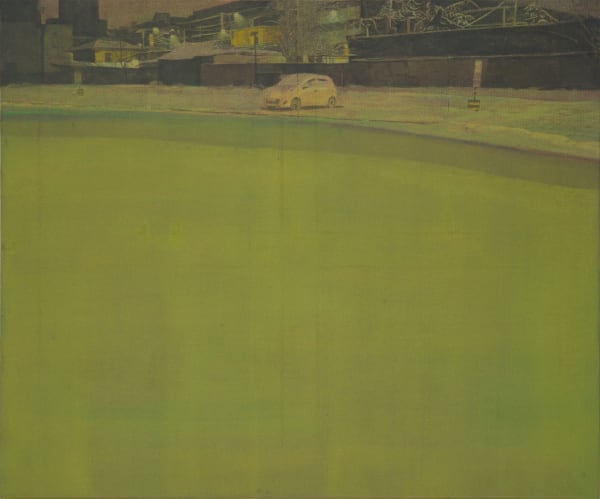

먹지로 캔버스에 옮겨진 이미지는 파리 오랑주리 미술관, 대구 수성못, 서울 선유도와 혜화역 등 권세진이 직접 마주친 풍경이다. 이번 신작은 작가가 1, 2년 사이에 본인이 찍은 풍경 사진을 사용했으며, 사진을 편집하거나 가공하지 않고 사진 이미지 그대로 풍경화에 담았다. 하지만 구체적인 공간적 특성은 중요해 보이지 않는다. 그는 자신의 그림이 실제의 대상을 그린다기보다는 사진 이미지를 재현하는데 가깝다고 말한다. 그리고 시간을 박제하는 사진 매체가 좋다고 말하는 작가는 사진을 ‘순수한 이미지’라고 명명했던 리히터의 말을 인용했다.

권세진은 이번 작품이 디지털 방식으로 찍은 사진에서 출발했지만, 마치 브라운관 TV로 송출되는 화면처럼 재현되길 원했다. 가까이 다가가면 거친 망점이 그대로 비추던 화면 말이다. 동양화를 전공한 그는 곽희의 <조춘도>와 같은 고전 회화를 좋아한다고 했다. 브라운관 TV의 화면을 재현하고 싶다는 것은 결국 고전 회화의 색이 바랜 비단이나 종이에서 느껴지는 깊이감과 시간성을 재현하고 싶었다는 말과 다름이 없다. 동양화의 현대적 해석이 전통적인 기법이나 관념을 재현하는 데 초점을 맞추고 있다면, 권세진은 동양화 화면에 켜켜이 쌓인 시간성을 재현하고자 한 것이다.

먹지를 이용해 풍경을 캔버스에 기록하는 그림은 선조들이 풍화작용으로 언젠가 사라질 석조문의 아름다운 글씨를 보존하려고 했던 탁본을 환기시킨다. 하지만 권세진은 오래된 과거의 유적 대신 현재의 삶을 조용히 관찰하고 기록한다. 고전 회화, 색이 바랜 사진, 브라운관 TV의 화면을 연상시키는 그의 풍경화는 마치 우리의 ‘현재’도 곧 ‘과거’가 될 것이라는 세상의 진리를 암시하는 듯하다. 기록된 풍경은 분명 그에게 ‘현재’였지만, 그림으로 재현된 ‘현재’는 이미 우리에게 (또한 그에게) ‘과거’이다. 이미지는 언제나 현재보다 우리에게 늦게 도착하는 법이다. 실제의 풍경 역시 다르지 않다. 현재의 풍경은 과거에는 없었으며 미래에도 없을 장면이다. 파란 하늘과 뭉게구름, 빛을 반사하는 황금빛 모래알, 고요히 흘러가는 강물, 유리창을 뚫고 실내를 비추는 햇살, 빠르게 달리는 버스 차창 너머의 노을. 그렇게 생각하니 조금 많이 슬픈 풍경이다.

Azur skies and cotton clouds, golden glitters of sand, a quietly babbling river, a ray of sunlight through the glass window pane, and the saturated dusk parallaxed on the far windscreen of a hasty metro bus. Something is sullen about these scenes. Our paths cross only for a moment before we must bid farewell in this reality bound by time. Somehow miraculously surviving, we are embraced, engulfed in the landscape for only the briefest of moments before it fades away into the mist. Perhaps we were drawn to the idea of creating images, a hopeful paddling against the merciless futility that time brings upon our reality. The etymology of image can be traced back to imago, meaning copy, imitation, likeness; statue, picture, often in the sense of the portrait of the deceased or a death mask. That paddling against the current, that desire to grasp at all that must fade, that need to prolong those moments in image; has been driving the history of art.

In his solo exhibition CMYK, Sejin Kwon presents landscape paintings with his variations on the rubbing takbon method. The method begins with a sheet of ink paper over the canvas, then and a printed landscape photograph is layered over the carbon paper, then marked over with form and shade using a common office-stationary ballpoint pen, such as Monami or Bic. The practice much closer resembles marking than drawing. After the markings, Kwon adds colors. The CMYK color model is a subtractive color model, an acronym for Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Key Plate: those are the colours used in the printing process. The sheet of ink paper is the Key Plate in this case, leaving only CMY colors. Kwon color-painted the details first and ended by plain-brushing color over the entire canvas.

2014 was the year he first used ink paper to transpose images to the canvas. His preferred means of painting was by tracing an image superimposed over a sheet of ink paper to leave a print on the canvas underneath. He prefers this method as it is most mechanical, removing as much subjectivity as possible from the artist’s side of the brush. Yet this does not absolve this process of all subjectivity. It is merely less subjective. The artist has already made spontaneous decisions on the weight and thickness of the print paper which will go over the ink paper, more decisions on the canvas material type, ballpen type, and how much physical pressure to apply while marking over the ink paper. Ink paper tracing can squarely transfer a photographic image unto canvas. However, contouring over carbon paper does not yield contoured lines on the canvas, because ink paper has a very limited number of prints. This severely limits the ability to contour with bolder lines with greaer nuance. Any sort of expression of the ball point pet must be applied in a single stroke of the ballpen, with dynamic pressure applied while tracing the image.

The copied images on canvas are sceneries that Kwon saw in person: the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris, Suseong Lake in Daegu, Seonyudo Island and Hyehwa Station in Seoul. For his latest works, Kwon used landscape photographs he took himself within the past two years. The photographs were ink-copied unto the canvas landscape as-is, without any editing or processing. Regardless of fidelity, the specific spatial characteristics seem unimportant. Kwon describes his paintings as being more about recreating photographic images than drawing actual objects. He prefers the photographic medium for its ability to taxidermy a moment in time, quoting Gerhard Richter claim that photography was “pure image.”

Kwon’s latest works started with a digitally photographed image, but the artist envisioned the image getting broadcast over waves on an analogue CRT screen television. Analog televisions with the hair-raising glow of the cathode-ray tube, the halftones completely visible to the naked eye. With an academic background in oriental painting, Kwon has an appreciation for classical paintings such as Early Spring painting (早春圖) by Guo Xi (郭熙, active 11th century Song Dynasty, 960–1279) His desire to recreate CRT television screens is like the romance of classical paintings tangible in the faded silk tapestry and paper. He wanted to introduce a sincere depth of expression and time. While modern interpretations of Oriental paintings focus on the reproduction of traditional techniques or ideas, Kwon focuses on reproducing the passage of time that is so viscerally tangible in the Oriental paintings themselves.

The landscape paintings use ink paper on canvas, an echo of our forefathers carbon-copying mason-crafted gate names to preserve the beautiful calligraphy of the written name. To offset his observation and record-keeping of things from the past, Kwon is also quietly observing and recording life in the present. Invoking the past through classical paintings, faded photographs, and CRT television screens, the artist seems to meditate on the unavoidable truth of our present becoming the past far too quickly. The photographed scenery was present for him when the photo was taken, but as time passes, the same photo becomes an image or reproduced present. As such, it is unavoidable that image arrives after the present. The actual landscape is also no different. This present landscape did not exist in the past; nor will it exist in the future. Blue skies and clouds, golden sand that reflects light, rivers flowing through the river, sunlight shining through the glass windows, and the glow beyond the fast-running bus car windows. Revisiting that thought, it feels much more sullen.